Opinion leaders

Opinion leaders:

Activists, story spinners, experts, organization leaders

Opinion leaders are those whose opinions are respected by others, with the effect that others adopt those opinions. There are three main kinds of opinion leaders: activists, journalists/influencers, experts, and organization leaders. All four have influence over policy directions in their areas of specialization. Organization leaders can include everyone from village elders to presidents.

Activists

Activists are sometimes journalists, experts, or organization leaders, but as activists, their prime contributions to fomenting opinion change comes from the motivation and resources they apply the issue in question. Social psychologists have found that those who speak more in a group problem solving context are more likely to emerge as the leaders of the group. So it is with activists. Their continual displays of interest in the problem and motivation to resolve it leads others to look to them for orientation and opinions. Moreover, when they belong to formal activist organizations they have the resources and legitimacy to spread their views more broadly.

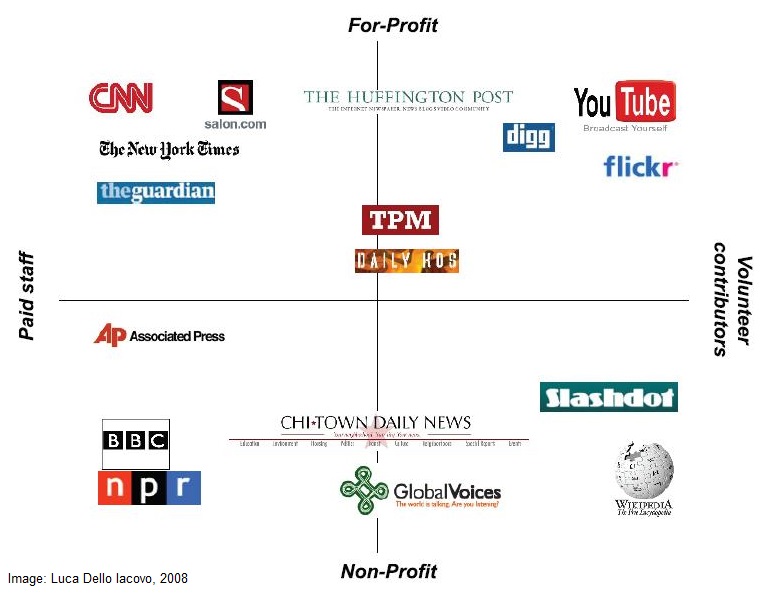

Story spinners: Journalists & social media influencers

News media tell stories. They put the facts of events into a narrative that has a problem and an actor responsible for either causing or solving the problem. They prefer narratives with conflict between good actors (heroes) and bad actors (villains). Too much complexity and nuance ruins the flow of the story.

When an organization’s activities remain of purely local concern and are not marked by conflict, journalists and social media influencers have little motivation to build narratives about them. However, when there is open conflict they will comment, trying first to make it a variation on an already familiar narrative. Only as a last resort will they construct a new narrative with customized good guys and bad guys affecting a new threat or disruption. Their stock of existing narratives inevitably reflects the political biases of their professional peers and their particular audiences. That’s how they decide who is good and who is bad.

When the activities of an organization attract the attention of the story spinners, it usually activates support or opposition from large numbers of the public who have already taken sides on the stock narrative to which the activity is being linked. Thus a 20 hectare construction project can elicit opposition from biodiversity proponents and a 20 hectare installation of solar panels can elicit support from climate change activists.

The Stakeholder 360 involves interviews with all those who have an interest in the activity and elicits their version of the story. This is strategically valuable for the organization because it shows what changes to the activity would increase or decrease support (i.e., the social licence) and what coalitions have formed, or could form in the future.

Experts

Experts are recognized by their peers as having acquired advanced knowledge in a particular area. When Robert Boutilier studied public opinion on the public policy of testing automobiles for polluting emissions in the Canadian province of British Columbia, auto mechanics were found to be influential experts. Many auto mechanics had begun telling their customers that the tests were being performed too frequently to have any beneficial effect on emissions. The government reduced the frequency of testing to avoid diffusion among the general public of the emerging narrative that the tests were a useless cash grab. Fortunately for the government, by learning the views of opinion leaders they avoided a politically damaging public debate before it had a chance to gain much attention.

Organization leaders

This may be the most important category because it includes government bodies and most of the local stakeholders.

Leaders of organizations and groups are also opinion leaders. In most organizations there is an executive group that develops a response to new policies or changes in activities that affect the organization. The leaders then communicate their position throughout the organization, usually in the format of a policy narrative. This is the top-down aspect of leadership. Where the organization’s leadership is elected, or emerges from popular alliances, the leaders must be responsive to shifts in preferences among the rank and file. Otherwise, they are replaced. This is the bottom-up aspect of leadership.

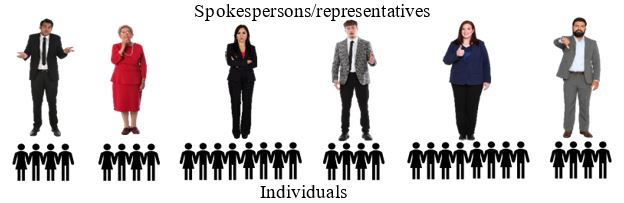

As a result of both top-down and bottom-up dynamics, the organization’s spokespersons can articulate either what the membership’s views will soon be, or what their views are shifting towards already. Moreover, they also tend to receive more attention from the media, which give them far more socio-political influence than randomly selected members of the public at large.

Groups usually have more socio-political influence than individuals

The Stakeholder 360® focuses on the group level. People have more socio-political impact when they work in groups. A spokesperson for a group represents the views of many individuals, while each individual taken separately, speaks only for themselves.

The groups do not necessarily have to be formal organizations. For example, in a study in Papua New Guinea, we treated clans as stakeholder groups and interviewed the elders as the representatives of the clans.