Politics of Policy

The policy and regulation development process

A broad view of the policy process

One of the primary justifications for developing a stakeholder strategy is its connection to the policy formation process, broadly understood. Environmental regulations and water permits are policies. Safety regulations, imposed by either government or employers, are policies. Boycotts are policies implemented by volunteers. The platforms of political parties are bundles of policies. Nepotism is a policy in practice, even when its existence is denied.

One of the earliest steps in the policy process is the development of a story about what needs to be changed, why it needs to be changed, who is to blame for the current situation, who will make the change, and what change they will make. These are the essential elements of a policy narrative.

The policy process encompasses public narratives and individual feelings about (1) the focal organization, (2) its activities, and (3) its sector or industry. We use the term ‘social licence’ to refer to stakeholder attitudes towards all three. If stakeholders have a negative view, they are more prone to imposing obstacles to the activity. In the extreme, they can shut down the focal organization. That’s why it’s called a ’licence’.

The lifecycle of policy controversies

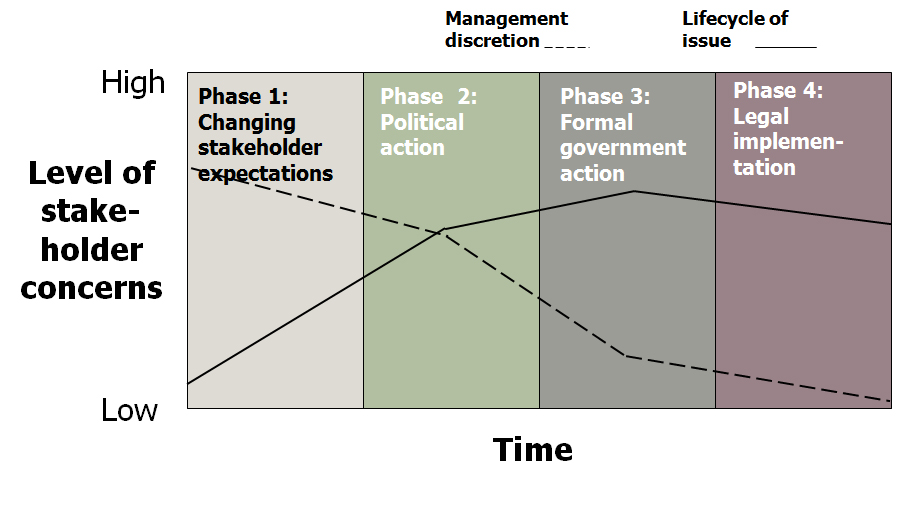

Every controversy is different, but many follow a general pattern across time consisting of four phases:

- Motivated stakeholders develop a narrative proposing a policy change (e.g., a regulation, a prohibition, a right).

- Promotion or agitation to build popular support for their proposal.

- Study and then action by government.

- Implementation of the policy change.

At each successive stage, the discretion of the organization whose activity is affected by the change is diminished. Not all policy narratives move from phase 1 to phase 2, or from 2 to 3. Often the narratives have to be modified in order to attract and accommodate more supporters.

Graph adapted from Post, J. E., Lawrence, A. T., & Weber, J. (2002). Business and Society: Corporate Strategy, Public Policy, Ethics (Vol. Tenth Edition). McGraw-Hill Irwin.

Policy controversies by industry and sector

The organization’s specific activity might not be controversial with local stakeholders but, no matter what the industry or organization type, there are stakeholders who criticize its activities. This becomes a strategic issue when critics can influence other stakeholders to undertake actions that either shut down the activity or raise costly obstacles to it. There is no one size-fits-all strategic response because those capable of erecting obstacles come in many different shapes and sizes. Sometimes they are grassroots movements. Sometimes they are well-funded, institutionalized movements from abroad. Other times they are elected politicians nervous about their popularity across a whole country, or even across an international trading bloc. Sometimes they are political opponents of the existing govenment whose only real interest in the activity is its potential to make their opponent unpopular. In still other circumstances they are cohesive communities with representative leadership. In all cases, however, these key decision-makers are either opinion leaders themselves, or are very sensitive to the urgings of opinion leaders.

You might not be interested in politics, but ...

Pericles said, “Just because you do not take an interest in politics doesn’t mean politics won’t take an interest in you.” Sensing that their activity might be become a political football in someone else’s dispute, organizations sometimes adopt a strategy of staying ‘under the radar’. With internet communications, this strategy is failing more often and more spectacularly. Trying to keep an organization’s activities hidden from view just feeds raw data to the conspiracy theorists. And to the credit of such theorists, a conspiracy of silence is still a conspiracy, even when there’s nothing to hide.

Some say that the essence of good community relations is establishing a personal relationship with stakeholders. Sharing a cup of tea, or a couple of beers, creates trust and understand, and is the only strategy you need. With luck, sometimes it is. The Stakeholder 360 was designed for situations where there are hundreds or thousands of stakeholders and dozens of organizations representing them, each with its own interests, sometimes conflicting. Personal relationships cannot be developed with all of them. In short, the S360 creates a socio-political roadmap for finding the shortest route to an organization’s goals when dozens of organizations have a stake it that goal’s success or failure.

|