Narratives and the SL

Narratives and the social licence

Narratives can both express the level of social licence granted by the speaker and attempt to change the level of social licence granted by others.

Narratives typically have a problem, a villain who is to blame for it, a victim of the problem, solution to the problem, and a hero who opposes the villain. The solution is often a policy proposed by the social actor who enunciates the narrative. The problems and the solutions can be chained together in cascades of causes and effects.

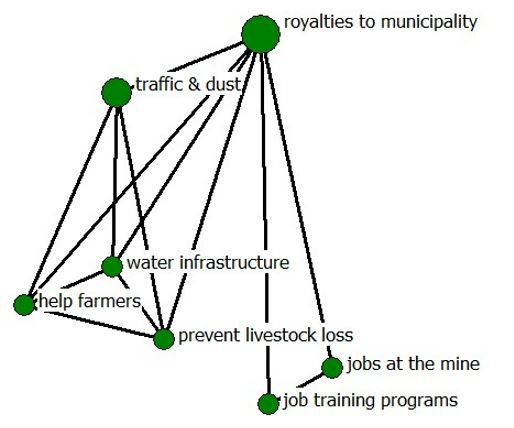

Chains of problems and solutions

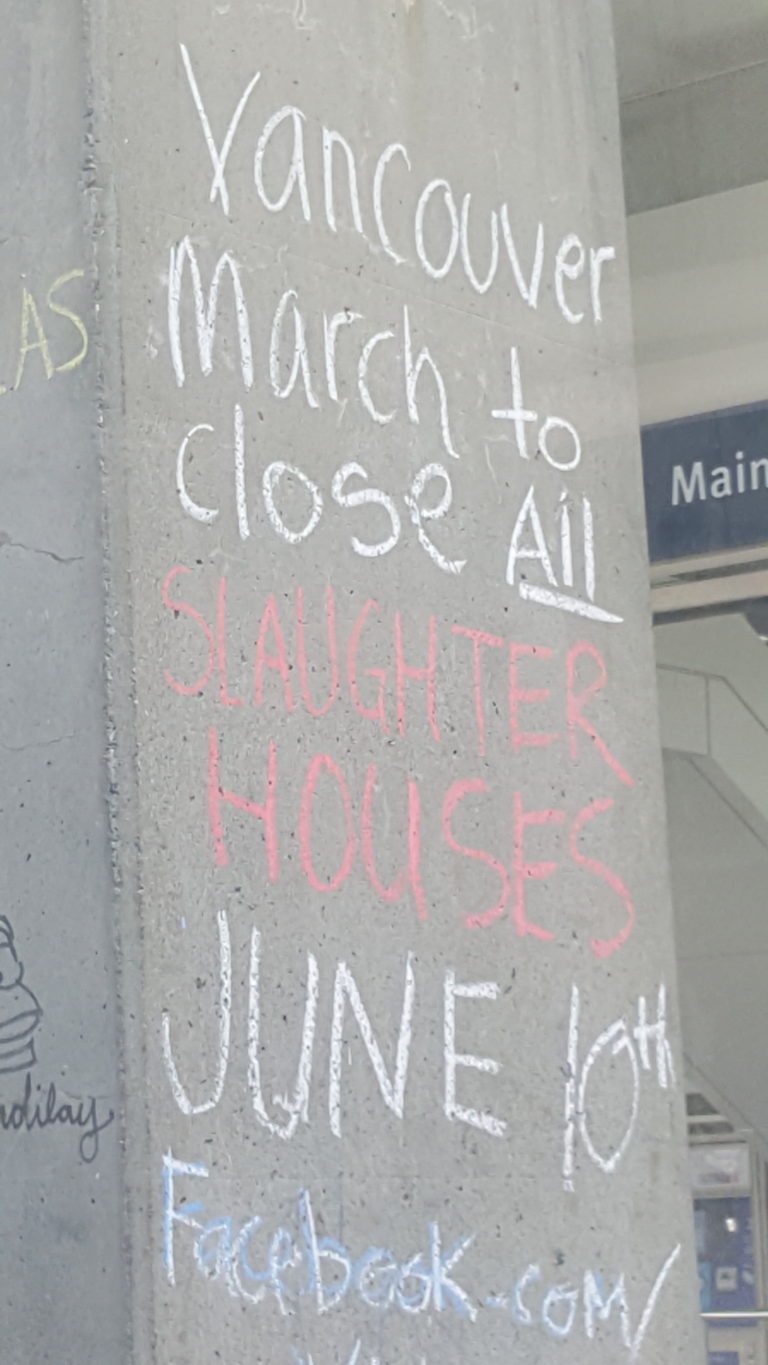

For example, there is a narrative that claims that the problem of climate change is worsened by the livestock industry which is sustained by meat-eating. Here the causal chain of problems goes from meat-eating, to sustaining the livestock industry, to worsening climate change. Similarly, the solutions appear in a chain starting with veganism, to a reduction of the livestock industry, to a reduction in climate change. Some narratives include empirical evidence for the purported causal links, but many do not.

SL of the villains

The social licence granted to the problem activities are obviously low in the eyes of the narrative’s proponents. In this example, the narrative’s proponents grant no social acceptability to meat eating or raising livestock. Likewise, the social actors performing the activites have had their social licence withdrawn, which really just means that that the narrative’s proponents disapprove of those activities. Applying the filter of narrative analysis, we see that meat eaters and ranchers are the villains of the narrative.

Victims and links to other narratives

The victim is all of humanity because of the effects on climate change. However, because climate change affects the whole planet, not just the humans, there is a link to narratives about biodiversity, ecology, and so forth.

The effects of ranching and meat eating on animals makes them victims too, which creates link to the narratives on animal rights and speciesism.

The important point to note here is that narratives exist in networks. Some are more central and influential in their networks than others. Some play more of a bridging role than others.

SL of the hero

The hero of the narrative is of course anyone who expresses it and/or agrees with it. Those who disagree with it, even if they are vegans, can be cast as villains and can even lose their social licence to express their opinions in some forums. Of course, there will be those who promote a counter-narrative that explains why promoters of the original narrative are the real villains. This creates something resembling a mirror image of vilification and self-congratulation. The nodes and ties that are shared by these two mirror image narratives represent points of conflict in the narrative network, as each side tries to place its own meaning upon those elements.

Networks of narratives

The study of networks of narratives is in its infancy. However, the field is likely to grow rapidly because tools like the Social Licence and Controversy Detector and Analyzer (SLaCDA) have automated the process of detecting problems/controversies and assessing the social licence level granted by any given speakers/social actor.

A network of problems identified in narratives about a mine.